I – The ViolinIn holding the violin, several areas of the body are brought into play simultaneously. For convenience of discussion, three main areas will be addressed sequentially. The violin is not so much held as it is balanced between and among three main areas: 1) the shoulder and collar bone 2) the chin and jaw 3) the hand. When properly balanced, there should be no feeling of pressure or tension from any area. It should feel almost like it's loosely floating, yet secure. Area One – Shoulder and Collar Bone The violin and our bodies must come to terms with one another in ways that are secure, and as comfortable and natural as possible – all the more so in view of the fact that the violin is not the most natural and comfortable instrument to play. In this regard, I strongly recommend that you do not use a shoulder rest – particularly of the type such as Kun or Wolf, which attaches at the sides and presents a rigid surface at one particular angle. If you have an unusually long neck, or a very un-broad shoulder, this might be necessary. But most violinists – and even more violists (due to the viola's higher ribs) – will not find it necessary, using my technique for holding the instrument. This is a bone of contention in violin playing and needs further explication. If you're already an advanced or intermediate player, long used to using such attachments, this may be a difficult change, and you shouldn't try it close to a performance or audition. The reasons not to use such attachments (which Heifetz called "scaffolding") – include the following:

If you're going to use an attachment, it is better to use a more pliant shoulder pad, such as "playonair" – or better still, a far less expensive sponge or piece of foam. You can experiment with different thicknesses and tailor the material more exactly to your needs. You can attach this material to your violin with a rubber band, or better still, (if it's not too thick), place it under your collar. Even if you don't feel a need for any of the above sort of support, it is strongly recommended that you place a thin pad or folded handkerchief over your collar bone. To find the proper angle of the shoulder and collar bone, do the following exercise – without the violin or bow:

Area Two – The Jaw and Chin How and where we place our jaw and chin over the violin is influenced by the type of chinrest we use – of which there are many. I highly recommend the "Kaufman" chinrest, or one similar to it. It is fairly flat, goes just to the left of the chinrest, and in some models (which I prefer) has an extended 'lip' which enables it to go partially over the tailpiece. Despite the name, most chinrests should support much of the jaw, and only end at the chin. Do not place only the chin on the chinrest. It should slope along the jaw to the chin. Many players develop an irritation – sometimes a serious inflammation – on the skin of their necks where they contact the chinrest ( –or the metal parts connected to the chinrest). I feel that this problem can often be prevented simply by covering the chinrest. There are some products on the market designed for this purpose, but a simple handkerchief may work just as well. However, I strongly advocate the following, which will add a good deal of added security to the violin hold: find a piece of thin (1/8") foam, or even better, a skin of suede leather about the size of a handkerchief, and use this material as you would a handkerchief – partly over the chinrest, partly covering the lower back of the violin. The part that covers the chinrest will function in the same way as the other materials. But the part beneath will provide a non-slip grip, so that the violin can be held securely and easily without pressure from the chin even in down-shifting. For the correct placement of the head and chin, do the following:

This is your basic position. There can – and ought to be – some deviation from this position in the course of playing. There are times when you may turn your head even more to the left, to concentrate on a more intricate, left-handed passage, or left-hand and bow coordination. At other times, such as for more expressive passages, or when playing from memory, you may wish to turn your head more to the right. You should feel at ease in so turning. Never clamp down with the chin. Once the left hand comes into play, the violin should mechanically resemble a board lightly resting on both ends on blocks. Relatedly, while the violin should usually be directly in front of you, you can bring it even more over the center (towards the right) when focusing on intricate left-hand passages,and when playing on the lower strings. When playing in the highest positions, and the tip of the thumb comes completely away from under the neck, the violin will move slightly to the left. When playing on the upper strings and when focusing, say, especially on broad bowing strokes, the violin can be more over to the left, affording more room for the bow to work. These deviations should not be extreme, and should follow from a relaxed, balanced hold. The violin should be held straight out and should never droop down, away from your chin. The violin should also be held relatively flat and more-or-less parallel to the floor and ceiling. There is – and should be – some degree of slope from the shoulder to the collar bone, but no more than anatomically necessary. Before approaching area three, it should be noted that to some degree we play with our whole bodies, and not just our fingers, hands and arms. When standing, the feet should be comfortably apart. The left foot should be basically aligned with the violin. The right foot should be slightly behind the left and turned slightly out to the right. We should usually have more weight on our left foot. In the course of playing, we may freely shift weight, but even when shifting weight, our basic cant should be to the left. We should always have a feeling of presenting the violin as an available and stable (if flexible) surface on which the bow may freely work. The bow comes to meet the violin, the violin should never push into the bow. Relatedly, it is helpful to occasionally bend slightly from the hip to the left. This facilitates a good angle for the lower strings and upper positions. (Heifetz and Milstein often did this.) When playing in a seated position our feet should usually be comfortably flat and in front of us, with the right foot, again, somewhat further back than the left – sometimes to the right of the chair's leg. It is technically alright – if not aesthetically so in performance – to allow both legs to be well in front with the feet crossed. Avoid keeping both feet well under the seat, as this can cause cramping. The chair should have both a back and a seat that are straight. It is important that most of the time you sit up straight, but comfortably against the back of the chair, allowing it to support your lower and middle back. Standing lends itself to a greater range of freedom of movement, as well as projection of sound. Health permitting, and depending on how much you practice, you should spend a preponderance of your practice time standing. However, it should also be tied to the repertoire involved. Usually you should practice standing what you would perform standing – i.e. solo repertoire; practice sitting what you would perform sitting – chamber and orchestral music. Area Three – The Hand The following discussion will be limited primarily to basic considerations in the 1st position with an occasional reference to other positions. The neck of the violin should (in the 1st position) rest lightly on the inside side of the thumb, supported on the other side by the lower side of the 1st finger, near its base knuckle. The thumb should point back, and the hand and fingers should be poised well over the strings, and the elbow should be well under the violin, pointing slightly to the right. The wrist should be comfortably straight and aligned with the forearm. It should not cave in toward the neck, nor bend out toward the scroll. This is our basic hand position. However, there are – and should be – a number of deviations and outgrowths from this basic position. The following is a non-exhaustive list of some of these:

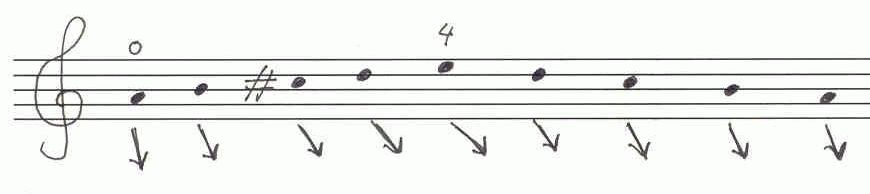

The basic determinant is each particular finger, around which the hand and arm will adjust. The finger should come on the string at an angle, so as to reach it easily and fall and lift readily. It should bisect the string slightly to the left of the center (– "left" as our palm and fingertips face us.) If the hand is not over the violin enough, and the elbow not under the center of the violin back enough, our freedom of movement will be seriously impeded. If too much over, we will end up playing on the fingernail – or too close to it. The length of each individual's arms and fingers will determine the exact angle in this regard; one with a shorter arm or fingers must be over more. However, even a player with long arms and fingers should, in general, have his hand fairly well over the fingerboard, and the elbow, well under the violin. Expressive vibrato passages once again prove mitigating: the angle of the fingers should be a little flatter (less curved) and more of the flesh of the fingertips used. It stands to reason that we should be most over on the G-string, and least over for the E-string. However, the angle of our knuckles and elbow also changes on any one string, depending on what finger we use. On any given string we are the least over with the first finger and most over with the 4th. When the 4th finger is on the string, all our knuckles will be fairly parallel to the neck. But we should not strive for this with the lower fingers. Thus in the first (or any given) position, we are least (though still properly) over with our 1st finger on the E-string, and most over with our 4th finger on the G-string. The ideal angle (to cite one example) for the 4th finger on the E-string is approximately the same as that for the 1st finger on the D-string. When playing double stops we must make balancing adjustments. As we play different passages across the strings – and with different fingers on any one string – we must instantly find the proper, and ever shifting angle. In this regard it is important not to neglect the pivoting motion of the elbow. This is important in general and aids the 4th finger in particular, in extensions. The pivoting elbow, in turn, frees up the hand and fingers. A simple exercise in this regard will help develop an awareness of this. The arrows are an approximation of the elbow's changing angle from the player's viewpoint. Practice the following on each string. Exaggerate at first, but eventually it should become very subtle, fluid and except for the 4th finger, barely perceptible.

This concludes some basic considerations of holding the violin. |